Here at the grocery store, wheeled carts are death. They weigh you down, keep you immobile; if you timed two people at a grocery store, one with a hand basket, another with a cart — gave them the same grocery list of ten simple items and set them on their way, the hand basket would have paid and walked out before the person with the cart found the last item.

Carts slow you down, and anything that slows you down and keeps you in the store longer is—to the store—a very good thing. You might see a display that catches your eye, or one of those hundred little red and yellow candy-colored packaging labels that alert you to something new.

Of course the grocery store is playing with fire. You could throw your hands up in frustration and walk out—or, more likely, complain about a disorganized store and next time go to Giant, or Food Lion, or Publix, or Whole Foods, or a whole host of other options. Or, you might give up the whole idea of preparing food altogether and instead settle on fast-food or your favorite corner bakery.

But if you are determined, like me, that you want to keep some food in your house—which isn’t an unreasonable thing to want—you may do as I do and time yourself. It’s a good way of keeping you on your toes, avoiding the two-for-one deal, and getting the process over with; because nearly everything about grocery shopping is a process. And not a particularly efficient one.

by Brendan Steidle

Counting Taps

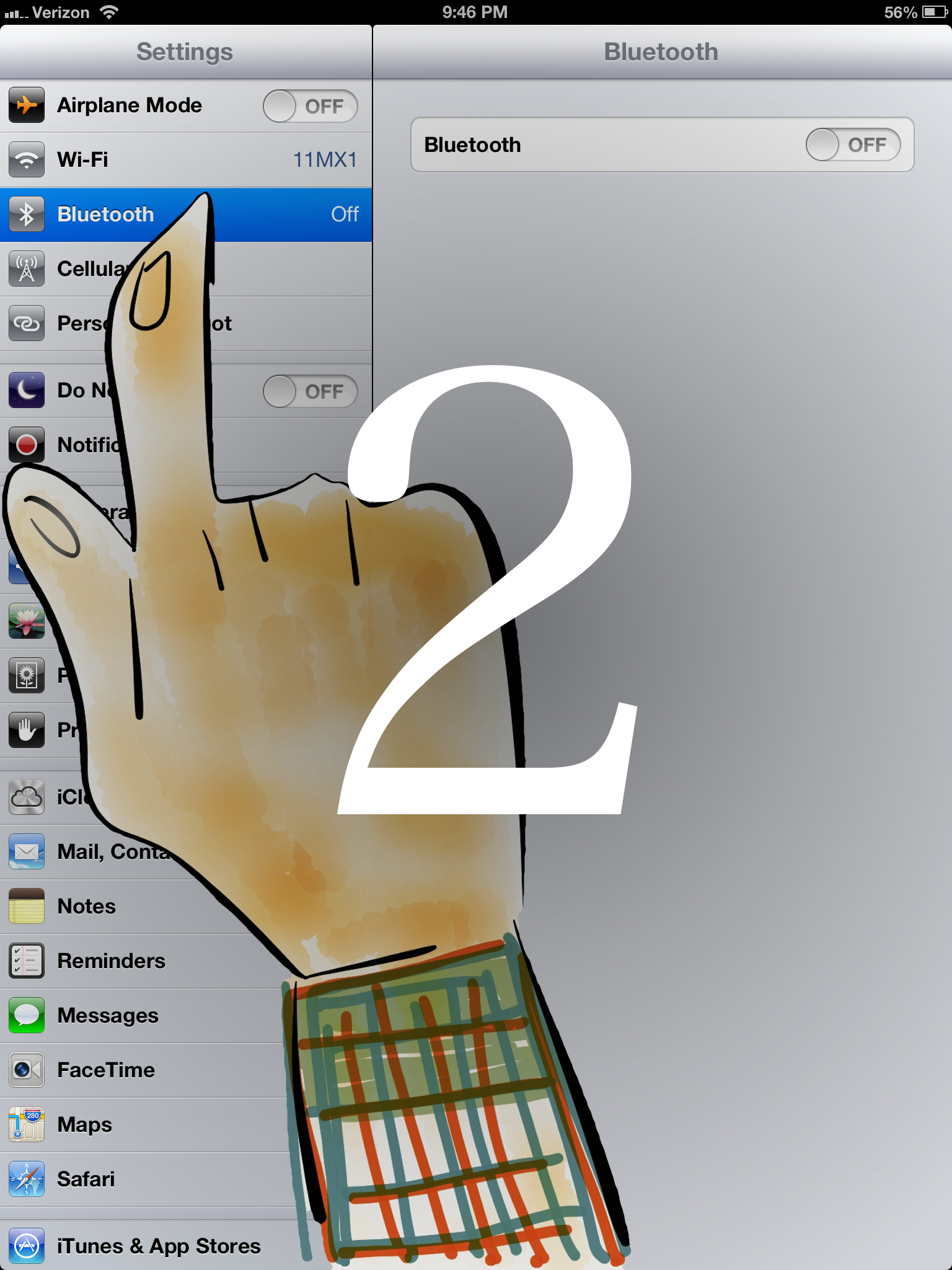

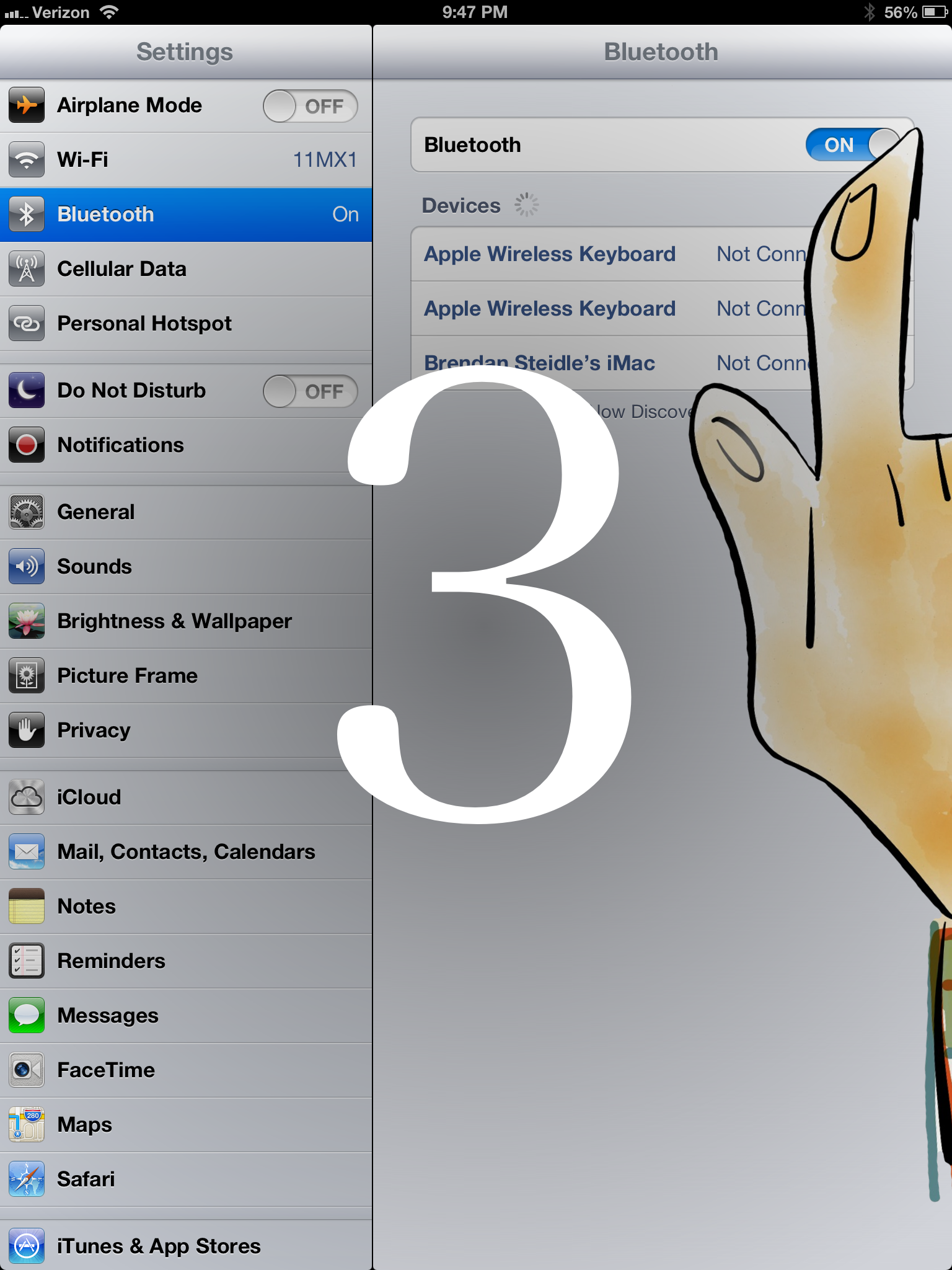

Steve Jobs was famous for demanding that his engineers count taps. He wanted a user of the iPod to be able to get to just about anywhere in three clicks. That dedication to simplicity continues even today in products like the iPad. For example, let's say you're using the iPad and you want to connect a wireless keyboard. You need to turn on Bluetooth:

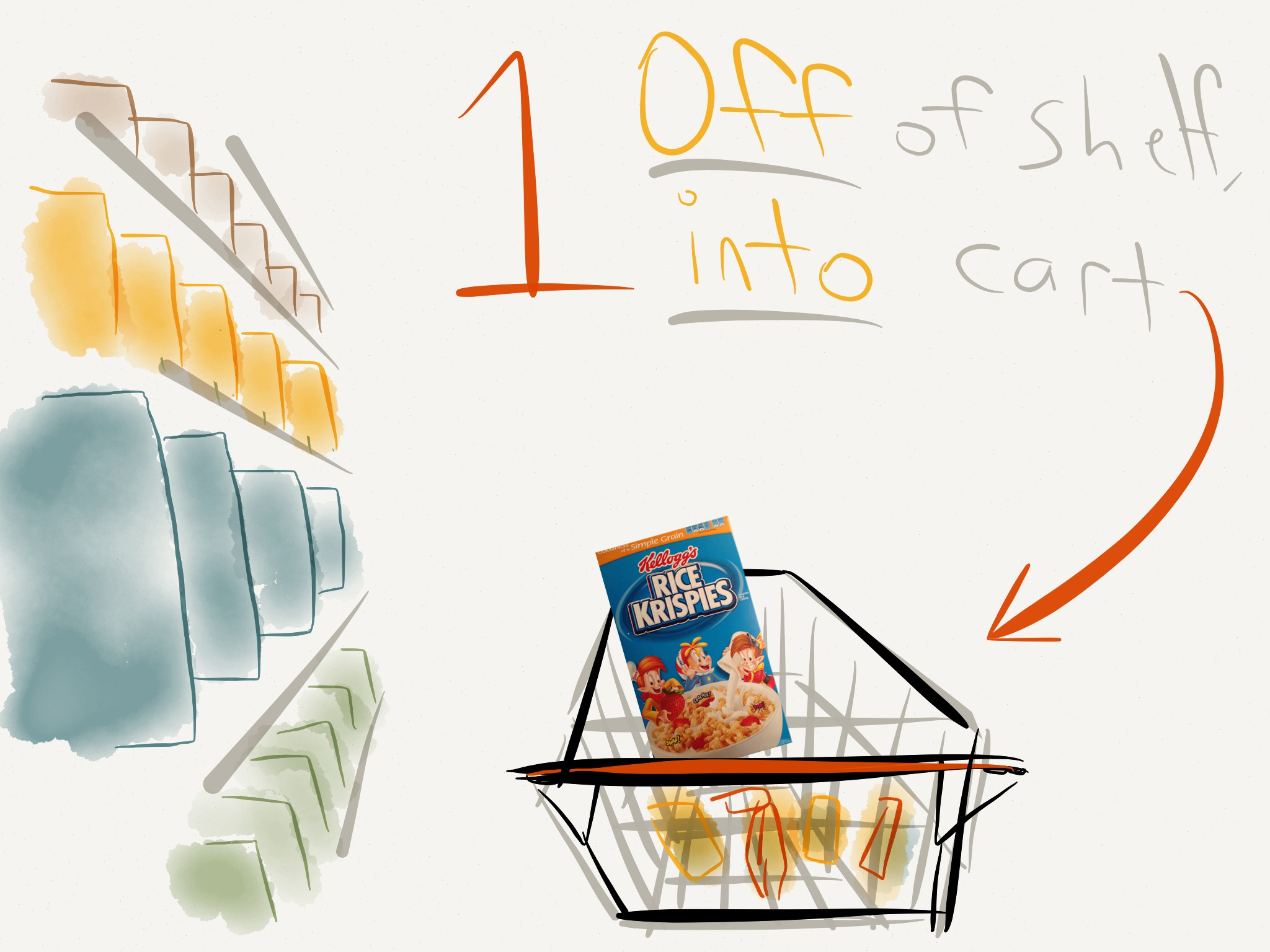

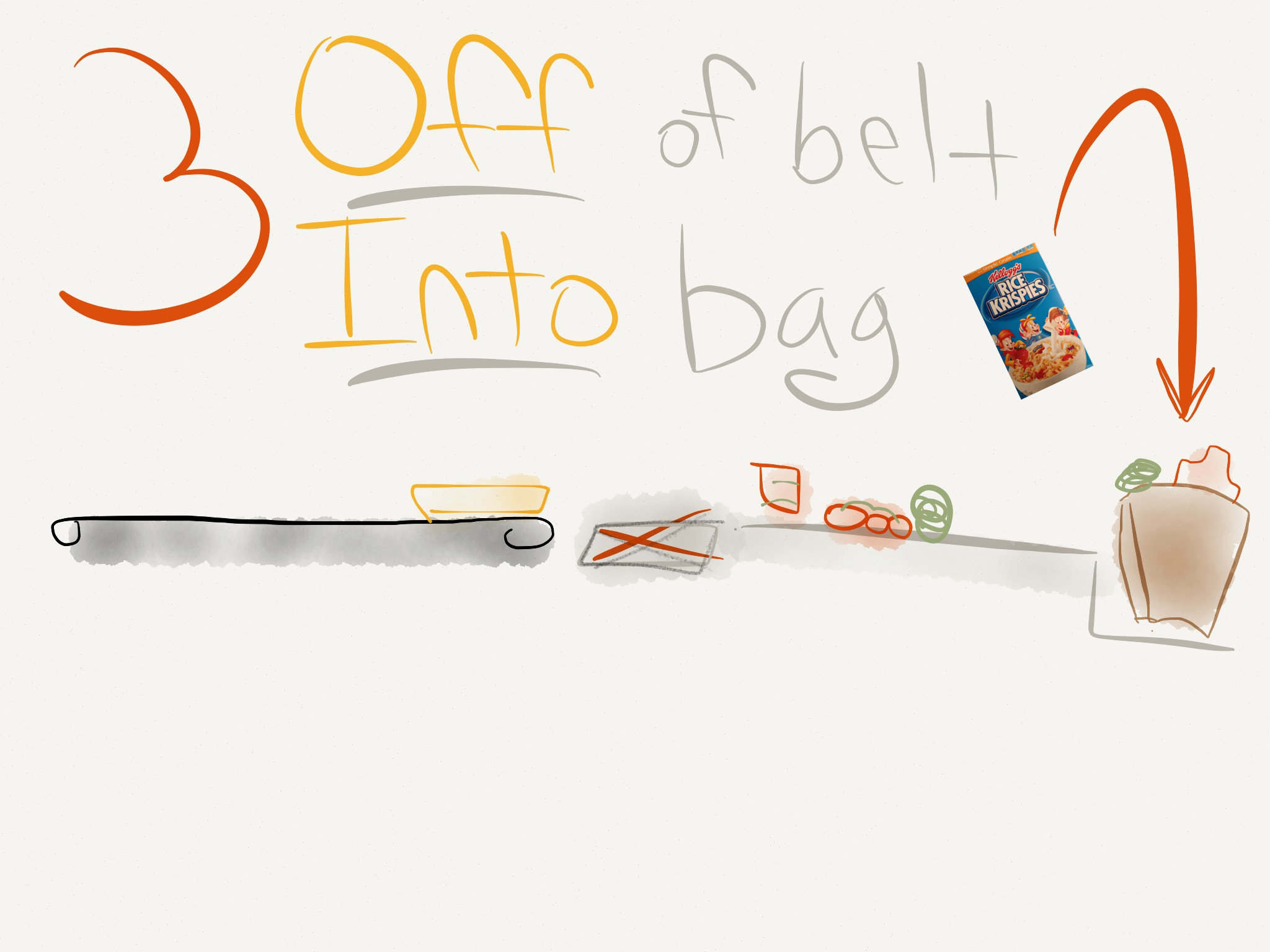

Compare that with the steps it takes to have a bowl of cereal:

Knocking out those first five steps in five or ten minutes is an impressive task. Especially considering the way grocery stores are organized. For example, take three common grocery items:

All are stored in the refrigerator at home, and yet here's where the average grocery store puts them:

These couldn’t be further apart and still be in the same building.

When faced with this kind of inconvenience, it’s easy to assume a conspiracy; the grocery store wants you to walk through all of the areas between the three things you need most. And that may be true to some extent—though the reality is probably one of these:

- The grocery store never thought to make it convenient

- These three items are refrigerated, and it’s easier to wire refrigeration units against exterior walls. This last fact may seem to exonerate the grocery store, but plenty of stores have refrigeration units in the center, including this one.

And true or untrue, it’s still inconvenient. This is, of course, just the tip of the iceberg. Try making any full recipe and you’ll be zigging and zagging across miles of floorspace, tracking and back-tracking through a network of disconnected aisles.

All of this begs a very good question: if grocery stores take too long to navigate, are poorly organized, poorly labeled, tax your patience checking out, and create bag after bag of plastic waste, why do we tolerate them? Is this the price we pay for putting food on the table?

A host of grocery chains have said no—and they’ve incorporated clever innovations: from integrated bars and mini restaurants, like Whole Foods, to the impeccably well-staffed and hip Trader Joe’s, and even mass retailers like Giant with Peapod, a service that delivers the groceries you need straight to your door. But these are all sustaining innovations, as Clayton Christensen would say, ideas that sustain the existing way of doing business, even if they might have the potential to do more. And they’re the exception, rather than the rule. And the rule today is the run-around.

Let’s rewrite the rules.

The process of getting your cereal from shelf to bowl is just too long. How could we cut some of those steps? Here’s two examples of stores that already do:

Target

At Target they’ve cut down a step on their side of the equation. Everywhere else, the conveyor belt is a four step process. Two steps to get down the belt and two steps to get scanned and bagged—with separate people doing the scanning and the bagging. But at Target they’ve combined the last two. Rather than push food aside to be bagged by someone else, they simply drop the food right in the bag. This is far more efficient — they’ve cut out a step.

7-Eleven

Steps at 7-Eleven have also been greatly reduced: You go to a 7-Eleven. Ask to buy a lottery ticket. The person behind the counter hands it to you. Done! You didn’t go to an aisle, find the ticket, pick it up, and take it to the counter—the item was there waiting for you. You might ask, wouldn’t it be great if every item was there waiting for you at the counter? Unfortunately, that would require a really big counter. And it would take a long time for the attendant to gather everything. After all, there’s a limit to what’s within arm’s reach. But there’s another way to look at it. Forget the attendant; the important fact is that you essentially purchased the item at the shelf it sat on.

The First Proposal

What about a grocery store where you purchase the item at the shelf it sits on, one where you bag the item at the moment you put it in your cart? Then you could simply wheel the cart out the door and away you go. No lengthy checkout process. No waiting in line. No putting groceries on the conveyor belt. Here’s how it might work:

- You walk into the store and slide your credit-card.

- Grab a cart with an iPad on it.

- Begin shopping.

- When you take an item off the shelf, the item triggers an RFID reader in the cart.

- The iPad mounted in the cart displays the item and its price. Inside the cart are bags already accordioned open and waiting. The bags at the back are cooled; the ones at the front are warmed to keep food fresh.

- You drop the item in and continue shopping.

- On checkout, the screen flashes your total cost and item list, visually displayed with pictures of the items the way they might appear on a countertop or shelf. If you don’t want an item, take it out of the cart and leave it at the store. Your cost visually goes down.

- Press “accept” or accept by walking out. Your credit card is charged.

- You take the cart to your car and place the bags in your trunk. Done.

This effectively removes the entire checkout process. It cuts the shelf-to-bowl list down by 30 percent. It is possible to implement with existing technologies and would require far less staffing. But it also opens up a few more possibilities:

What if when you took the bags home you didn’t have to take the items out of their bags? What if you just slid the bag onto a special rack on your shelf, or into a drawer in your refrigerator? This would require creating containers that are light and transparent—so you can see what’s inside—and that can be slid onto a shelf, fit into a refrigerator or freezer, or hung on rungs in a pantry. That said, this idea would encourage wider adoption of reusable bags and cut down an extra step in the kitchen.

Ever walk up an aisle to grab milk, turn the corner and find that the next item on your list is back down that same aisle? It’s hard-enough to find things in the grocery store; it’s almost impossible to find everything in the right order —but that’s the ideal: to never have to back-track up the same aisle again. With the use of the iPad, some intelligent store mapping, and a pre-loaded grocery list, that might be possible.

Imagine emailing your list to the store before you arrive. Then the iPad could order those items according to the way you’d come across them, directing you to just the aisles you need to walk down —1, then 3, then 4, 5, and 6, then 12—and better yet, the screen could alert you with a big red arrow when you passed the item on the shelf.

Maybe you could even have little lights on the shelves that lit up to showcase just the product you need. What’s even better; you could save your shopping list for the next visit and make changes to it then. You could even build an active cookbook based on recipes you send. In this model, rather than emailing the store a grocery list, you could send the store links to recipes you found on the web. That way, whenever you send or mark a recipe—from any site you visit—the system searches through the text and parses out all of the ingredients, adding them to your list.

But what if the recipe calls for eggs and you already have eggs? The web app could keep track of your past purchases and based on common usage statistics, the app could make intelligent inferences about what you already have and how much you probably have left. A simple mobile or web app could help you do inventory in your own pantry before you get to the store. Better than sending recipes directly, the store could create an app that installs a bookmarklet in your browser, similar to Marco Arment's Instapaper, so that with one click on any website, the recipe is captured and its ingredients added to your shopping list.

Grocery stores may protest the last idea; because they don’t really want you to buy everything on your list—they want you to see new things, to notice their promotions and be swept up by some new marketing ploy. That’s why they place samples at the end of the aisle and advertise specials. In fact, the average supermarket has about 100 promotions a week. That’s not to say they’re all successful. One recent study found that only about half of the promotions that manufacturers pay for are placed on time or executed at all. Here’s a better way:

Drop a jar of mayonnaise into your cart and the cart displays a message: “Oh, you’re buying Hellmann’s Mayonnaise? Why not head over to the deli right now and get 10 % off Boar’s Head Ovengold Turkey Breast?” Or: “Do you know this great recipe for tuna salad? You already have three of these ingredients; here are the other two you’ll need; would you like to add them to your shopping list and get five percent off now?”

It would be a great way to introduce people to new recipes and reduce the friction between a promotion and the actual purchase of a new product; because most of the time, even if you do see a coupon that catches your eye, how often do you remember to actually use it and buy the item?

In moderation this may be helpful; too much would certainly get annoying. The store would have to use discretion, restraint, intelligence and maybe some analytics. For example, your grocery profile might remember that you bought that mayonnaise to make sandwiches three months ago and so may ask, as you pass it in the store: “Are you low on mayonnaise? Get 10 percent off now.” The algorithm could be based on average shopping habits, or on detailed analysis of your buying history at the store. This is the kind of thing that makes some people uncomfortable, but anyone who has ever run out of milk and tried to eat their cereal with cold water will appreciate well-timed suggestions.

Wouldn’t it be great if your grocery store could help you to eat healthier? What if you indicated that you were on a diet; so that when you entered “milk” on your shopping list, the cart directed you to skim milk; when you indicated eggs, it took you to egg-beaters; when you put down “chips and dip” it intelligently sent you to blue-corn chips and hummus? And when you put cookies in the cart the screen flashed yellow and asked: “Do you want to try one of these healthier alternatives instead?” — and provided enticingly-photographed healthy snack alternatives, from low-fat cookies to sliced apples with honey. You can select one of the items onscreen, or hit one of two buttons: “No Thanks” or “The Healthiest,” which directs you to the healthiest alternative on the list.

This system, of course, would be an optional feature—enabled by the individual. And it might be scaled up or scaled down; from offering alternatives to an existing list, to calculating exacting diet standards and calorie intake based on body mass, eating habits, and age or allergens (for example, those with Celiac disease). The idea could make it a lot easier for people to make more, informed healthy choices. It would also demonstrate that good eating doesn’t have to be about the tedium of counting calories or compromising on taste and variety.

A spin on the “dietician” program could be one designed for families on a budget. Rather than entering your personal dieting goals, you could enter something like: “I need to feed a family of 4 for two weeks on $250.” It could then spit out a variety of optional meal combinations and then populate your grocery list accordingly. This could help struggling families manage their food budget intelligently, ensuring the proper balance of nutrition while steering them towards the best values and best variety available.

Why walk the aisles at all?

As we walk further and further down the path of innovation, the store becomes more and more active in helping us figure out what to buy and what to eat—and why shouldn’t it help us make informed, healthy, economic choices? But the further we walk along this aisle, the closer we get to a new question: why walk the aisles at all? If the store is going to be presenting us with entire suggested recipes, why do we need to walk up and down aisles to gather them together? Couldn’t the store do this for us?

Welcome to Kitchens

The first thing you notice when you walk in is that there are no aisles. No merchandise. No carts of any kind. Instead, it’s a wide open space. And set like islands scattered across this space are kitchens. Five in total:

- Italian

- Asian

- Mexican

- Vegetarian

- American

Each kitchen has a distinct look and feel: textures, tables, countertops. A unique feel and a unique aroma. The kitchen isn’t for show; it’s actually being staffed and overseen by its own chef. One chef for each kitchen. The chef oversees the preparation of seven unique meal-combinations, one for each day of the week. This food is provided free to taste on a countertop and constantly replenished so that guests can try the food currently on tap. The menu changes once a month and is selected—not by the chef on site, but by a master-chef at the Kitchens corporate headquarters. This is true for every kitchen chef except for one.

Guests visit each kitchen, tasting the food on tap until they are satisfied and ready to make a choice. Let’s say you choose Italian, because you particularly like the taste of the Penne Linguine. You alert a member of the kitchen staff, who asks you five questions:

- For how many people?

- For how many days?

- Any special requirements?

- Do you need a prep package?

- Return in store or mail?

You answer:

- A family of four

- One week

- One member is allergic to nuts

- Yes, we’ll need a prep package

You’re given the total cost: $150. You pay there with your credit card and are asked one last question: Which food would you like to have as a complimentary thank-you while you wait?

You select the dessert Tiramisu.

Ten minutes later—or less—a sturdy box on wheels, about the size and shape of a moderate suitcase, is rolled up for you to take home. The wheels make it easy to get to your car, where the box fits snugly in your trunk. The package is easy to handle and rugged enough for public transportation. If you have a long commute, there is no reason to worry, because the box is designed with special cooling sections to keep items crisp until you get home.

Inside is every ingredient you need to make all seven meals to feed a family of four for seven day. You’ll find pasta and fresh herbs and spices grown in the store garden; you’ll find a hard rock of parmesan cheese and a white wine vinaigrette; you’ll find everything—everything you need straight down to the pepper you’ll ground out—and nothing more. Just the right amount of spices, just the right amount of butter that the recipes require.

Also inside is a preparation (or prep) package, which includes a colander, a cheese grater, mortar and pestle, and any other special item necessary to preparing the recipes. And of course you get the recipes, too, available as an app for an iPad, Android, or Microsoft Surface, or on any mobile phone. The app has step-by-step recipes for every menu item, including video-instructions filmed at Kitchens headquarters by the Italian Master Chef. At the end of each recipe is a button for you to provide direct feedback by typing or recording an audio message. And if you don’t have a mobile device, one can be included in the preparation package.

At the bottom of the box is a postage pre-paid box for mailing back the preparation items such as the colander, cheese grater, and other materials. And a small case with two German chocolates and a card that says simply: “Thank You.”

***

Each chef is overseen by the store’s Managing Chef, who also operates the American Kitchen. The American Kitchen is the only one where the chef is in charge of designing and preparing his or her own recipes. This means that at every store location, there is something new and unique to taste. The American Kitchen is also where local customers can submit their own recipe requests, or visit on weeknights to enroll in cooking classes.

***

The cost of food at kitchens is quite affordable. Here’s why:

First, there are fewer units to stock. The average grocery store stocks about 39,000 items. That’s a constant headache to manage, to ship back and forth, to balance and make sure everything’s not damaged or out-dated. About 1 percent of items in the average grocery store are damaged or out of date. With fewer items to stock you save stocking and managing time, you reduce the incidence of damage and lost goods, and save the shopper all of the time and trouble of looking for items.

Second, there’s no costly checkout process. No registers or bags at all; no carts to gather in the parking-lot.

Third, the food itself is cheaper. How? Because the store doesn’t stock name-brand foods; name-brands don’t matter in this context. All that matters is quality and convenience, so the store is able to source food like a restaurant does; fresh, directly from the producers. The food doesn’t need to be individually packaged or wrapped or purchased at a high premium because it happens to have the Heinz name emblazoned on the side. It can be bought in bulk and sold in bulk, or whatever quantity that chefs demand.

In the end, what this means is you get an incredibly streamlined shopping experience; one that encourages you to try new and exciting foods, that helps you to cook and prepare delicious recipes, and to interact with a staff composed, not of people who stock shelves—but of people who love food; chefs who know their way around the kitchen. And who can help you learn, too.

The Elephant and the Panda

Today, most of us find ourselves somewhere in between the two extremes of the elephant and the panda: gathering food for too long, and eating too much of it for too few nutrients. Part of this, it's said, is the fault of our lifestyles. Of a culture of over-booked time and under-priced junk-food. But I can't help but think that some of it's just a missed opportunity.

If a panda bear designed a grocery store, what would it look like? It would probably be filled with bamboo; plentiful stalks of bamboo down every aisle, in different shapes and forms, with different tastes; maybe one that is sweet, one that is salty, one that is crispy and juicy and green, and one that is dry and smoky and sharp. A panda grocery store would be a very successful endeavor, because it would add variety to what undoubtedly must be a very monotonous diet.

Likewise, a grocery store designed by an elephant would serve to improve the experience of searching for food. It would bring all of the food needed under one roof, so that the elephant didn't have to wander from place to place to find a full meal. This, too, would be successful—because an elephant could spend his day browsing the aisles of the store, certain of a fresh find.

These two stores would be very good at replacing one way of gathering food with another way of gathering food; but they would be very bad at actually improving the lives of either the panda or the elephant. After all, it doesn't matter what flavor the bamboo is; a panda still needs to spend all day eating it. Just as an elephant still needs to consume his 250 pounds.

Where did these stores go wrong? They went wrong because they tried to replace an action, rather than serve a value. There's a lot of ways to improve the eating of bamboo; but pandas aren't actually looking for bamboo, they're looking for nutrients that can give them energy to do everything else they need to do: have kids, raise a family, and keep up on gossip. The panda grocery store missed an opportunity by missing this value; our stores are missing the same thing.

Grocery stores today give us more options, spread across greater area, locked behind long processes and false values: extolling the value of taste which is really just a byproduct of nutrition; or the value of speed which is really just a byproduct of satisfying hunger.

In the end, the real question is simple: how can we spend more time discovering great food, and less time looking for it? How can we spend more time enjoying healthy meals, and less time gathering the ingredients?

I firmly believe that anyone who sells food is in a position to help us with this, and that whoever does will not only succeed in achieving greater profits, but could actually change the way we live. Because no purchase is more important than food. No matter who you are, elephant or panda, cook or consumer, you gotta eat.

Notes and Sources

The story of Steve Jobs counting clicks in the design of the original iPod is recounted in Chapter 30 of Walter Isaacson’s “Steve Jobs.” From the section titled “That’s It!”: “Once the project was launched, Jobs immersed himself in it daily. His main demand was ‘Simplify!’ He would go over each screen of the user interface and apply a rigid test: If he wanted a song or a function, he should be able to get there in three clicks. And the click should be intuitive. If he couldn’t figure out how to navigate to something, or if it took more than three clicks, he would be brutal.” http://books.simonandschuster.com/Steve-Jobs/Walter-Isaacson/9781451648539 For an alternative view on the "counting clicks" theme, check out the work of Lukas Mathis: "A great user interface is not one where each goal can be reached with the smallest number of clicks possible, or where the user has to pick from only a small number of choices at each step, but one where each individual click is as obvious as possible...As long as users feel that they are getting closer to their goal with each step, they don’t mind drilling down into a deep hierarchy." http://ignorethecode.net/blog/2012/12/17/satisficing/

The quote by Ron Johnson is from JCPenney’s September 19, 2012 Open House Tour. It appears in the CEO Commentary Transcript on page 13. The quote is in the context of JCPenney’s implementation of RFID. Johnson discusses how Penney’s already has 40% of its tickets on RFID. Eventually they want to get to full RFID so the customer can check out by him or herself. Johnson: “Because having full RFID lets us have perfect control in counts of our inventory. It lets us know within a few feet where everything is, when we have to find it for the customer. It lets us replenish more accurately and more quickly, but it also lets the customer check out in 25% of the time. And the transaction is the worst part of the retail store experience, and it has been forever.” Johnson previously led Apple’s retail stores, taking them from inception to become the most successful retail stores in the world. http://ir.jcpenney.com/phoenix.zhtml?p=irol-eventDetails&c=70528&eventID=4836951

Figures and details on supermarket promotions are from the January-February 2012 issue of Harvard Business Review in a story titled “Why ‘Good Jobs’ Are Good for Retailers” by Zeynep Ton, a professor in operations at the MIT Sloan School of Management. The industry study cited is from 2008 by the In-Store Implementation Share-group. On page 128: “A typical supermarket is a complex operating environment. It carries close to 39,000 SKUs, ranging from an Idaho potato to a 6.4-ounce tube of Crest fluoride anticavity toothpaste with tartar protection. The store receives multiple deliveries every day from manufacturers and its own distribution centers, and store employees shelve much of the merchandise. It has about 100 promotions a week and serves close to 2,500 customers a day.” http://hbr.org/2012/01/why-good-jobs-are-good-for-retailers

Statistics on elephant eating habits are from the San Diego Zoo: http://www.sandiegozoo.org/animalbytes/t-elephant.html

Statistics on the Giant Panda are from the Smithsonian National Zoological Park here in Washington, D.C.:http://nationalzoo.si.edu/animals/giantpandas/pandafacts/default.cfm I took both of the photos of the elephant and Giant Panda courtesy of the park. The panda in the photo is Mei Xiang, a female born in 1998 at the China Research and Conservation Center for the Giant Panda in Wolong, Sichuan Province, China. She weights about 230 pounds, or a little less than the average elephant eats in a day. You can find more information on her at: http://nationalzoo.si.edu/Animals/GiantPandas/MeetPandas/default.cfm